福島第一原発 がある双葉町の前町長 われわれは「事故は絶対に起こらない」と言われてきた

2014年1月17日 東京から放送

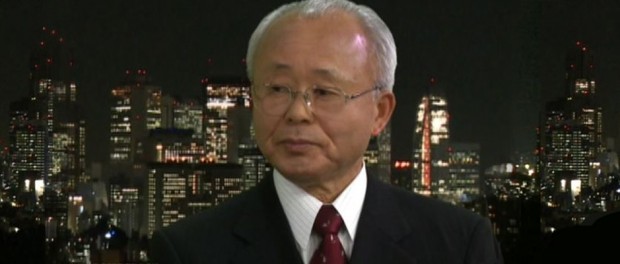

福島第一原発がある双葉町の前町長

われわれは「事故は絶対に起こらない」と言われてきた

日本政府は数日前、国内の原発を再稼働する動きを見せました。この動きで、脱原発運動がより高まっています。「これは日本だけではなく、世界の問題です」と首相官邸前の抗議者の一人カトウケイコさんはデモクラシーナウ!に語りました。彼女は、来月の都知事選では、候補者の原発に対する態度が争点になる事を期待しています。

【GUESTS】

Katsutaka Idogawa, former mayor of the town of Futaba where part of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant is located. The entire town was rendered uninhabitable by the http://ebaconline.com.br

英語版

Mayor of Town That Hosted Fukushima Nuclear Plant Says He Was Told: “No Accident Could Ever Happen”

【TRANSCRIPT】

拡張するThis is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: Music from the film Nuclear Nation: The Fukushima Refugees Story. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. This is the third day of our broadcast from Tokyo, Japan, and the final day. We are talking about moving in on the third anniversary of the Fukushima disaster. Nineteen thousand people died or went missing on that day, March 11th, 2011, and the days afterwards, when the earthquake triggered a tsunami, and three of the reactors at the Fukushima nuclear power plant melted down.

We’re joined right now by Futaba’s former mayor, Katsutaka Idogawa. For years, he embraced nuclear power. Now he has become a vocal critic. He is featured in the film Nuclear Nation.

We welcome you to Democracy Now! And thank you for traveling two hours to join us here at the studios of NHKInternational for this conversation. Mayor, explain what happened on that day—special thanks to Mary Joyce, who is translating for you today—on that day, March 11, 2011, and the days afterwards, when you decided it was time for the thousands of people who lived in your town, Futaba, to leave.

KATSUTAKA IDOGAWA: [translated] On that day, there was an earthquake of the scale of something we’d never experienced before. It was a huge surprise. And at the time, I was just hoping that nothing had happened to the nuclear power plant. However, unfortunately, there was in fact an accident there. And then I worked with the many residents, and thinking about how I could fully evacuate them from the radiation.

AMY GOODMAN: You made a decision to evacuate your town before the Japanese government told the people in the area to do this, but not before the U.S. government told Americans to leave the area and other governments said the same.

KATSUTAKA IDOGAWA: [translated] Yes, the Japanese government’s information to evacuate became much later than that, and my mistake at the time was initially waiting to hear that. If I had made the decision even three hours earlier, I would have been able to prevent so many people from being so heavily exposed to radiation; however, as a result of that, unfortunately, several hundreds of people were directly affected by this radiation.

AMY GOODMAN: Where did you decide to move the whole town?

KATSUTAKA IDOGAWA: [translated] I was originally thinking about this at the time of the earthquake on March 11 first. However, at first, I was waiting to rely on the government information to decide the timing for this.

AMY GOODMAN: And so, you moved the town to a school in the outskirts of Tokyo, is that right? The entire town to an abandoned school? Explain how you set up your government, your whole community, in this one building.

KATSUTAKA IDOGAWA: [translated] Right at the start, we were unfortunately not able to evacuate all of the residents, and some actually did remain within parts of Fukushima prefecture. And as a result of this, there was actually a gap created between those who were still remaining within the greater Fukushima prefecture area and those who evacuated to Saitama, outside of Tokyo. And the reason for this is we had no access to communication, to information, to mobile phones.

AMY GOODMAN: And so, how long did people stay? How many people were in this school? And what role did the government play? How has the government helped the refugees?

KATSUTAKA IDOGAWA: [translated] We were able to evacuate around 1,400 of the residents to Saitama prefecture, outside of Tokyo. So they were saved from the initial first exposure, the most serious exposure to radiation at the time. But many of them, unable to deal with the situation, gradually started to return to different parts of Fukushima prefecture.

AMY GOODMAN: You have not returned back to your town?

KATSUTAKA IDOGAWA: [translated] Yes, I am still living in evacuation away from the heavily radiated areas.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about the meetings that you have had with the government? You have had a remarkable association of nuclear mayors in Japan, the mayors who live—who preside over towns that have nuclear power plants in them.

KATSUTAKA IDOGAWA: [translated] From before the accident, we had always been strongly calling upon the government, and also TEPCO, to make sure that no accident was ever allowed to happen. And they were always telling us, “Don’t worry, Mayor. No accident could ever happen.” However, because this promise was betrayed, this is why I became anti-nuclear.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to go to a clip from Atsushi Funahashi’s new documentary film about the former residents of Futaba, where the Fukushima Daichi nuclear power plant is partly located. The film is called Nuclear Nation: The Fukushima Refugees Story. And we’re going to go to a part of the film that shows a part of this remarkable meeting of government officials with the atomic mayors, the nuclear mayors of Japan.

BANRI KAIEDA: [translated] The future of energy production and Japanese energy policy is currently being debated, and this is something we’ve communicated to you. Regarding the details of this review, I believe it’s important to clearly define the terms as soon as possible. Thank you very much.

MARC CARPENTIER, Narrator: The industry minister leaves his seat in the first five minutes.

GOSHI HOSONO: [translated] The central and prefectural governments are working on the annual health check guidelines. Based on what we’ve researched until now, the impact of radiation on children appears negligible. However, we will endeavor to keep you apprised of any developments.

MARC CARPENTIER: The nuclear crisis minister follows suit, citing official duties.

CHAIRPERSON: [translated] And now, we’d like to open the floor for comments. Please raise your hands. OK, go ahead.

MAYOR KATSUTAKA IDOGAWA: [translated] I’m representing Futaba. I want to know why we’re being made to feel this way. It’s frustrating. What does the nuclear power committee think? When you came and explained it to us, you lied, saying it was safe and secure. But we, who trusted and believed you, can no longer live in our own town.

AMY GOODMAN: That last voice was the mayor at the time of Futaba, Katsutaka Idogawa, who is with us today in our Tokyo studio. Futaba is where part of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant is located. He was speaking, addressing this meeting of government officials and nuclear mayors from around Japan in August of 2011. You just heard, oh, the voices of Goshi Hosono, who was the nuclear crisis minister of Japan, and Banri Kaieda, a minister of the economy, trade and industry. And after each of them spoke, they politely took their leave of the room before the mayors could address them, so they did not hear the Futaba mayor’s statement about the lies from the government. Talk about that particular meeting.

KATSUTAKA IDOGAWA: [translated] At the time, we were calling for a strong response and attention from the government since the disaster. However, they didn’t even try to listen to what we were calling for. And they continued to not even try to make efforts to fulfill their responsibilities or promise to us. And so, they continued to appear before us, those who were suffering directly from the disaster, but instead of listening to something which would maybe be difficult for their ears to hear, they would just leave the room, not even listen to us at all. And within those who were left in the room were some government officials, including some who were directly the ones who told me that no accident would ever happen. However, no matter what I would try to appeal and say to them, it would not have any effect, so instead I turned around and appealed and spoke to my colleagues, my fellow residents, and I tried to tell them what was really happening, the situation.

AMY GOODMAN: Former Mayor Katsutaka Idogawa, you were a fierce proponent of nuclear power. You were pushing for two more reactors to be built even closer to Futaba than the others. You were proud of getting tens of millions of dollars for your town for hosting these reactors. How did you make your transition to being one of the most vocal government officials against all nuclear power?

KATSUTAKA IDOGAWA: [translated] I had been supporting the nuclear power plants in our town on the condition that no accident, no disaster, would be allowed to occur. It was not necessarily that I was actually totally in favor of the nuclear power plants; however, the situation that was in places without the nuclear power plants there, our city would be losing the financial benefits and perhaps unable to go forward economically. The city was actually on the brink of bankruptcy beforehand. And so, in order to try and prevent the city from going into this kind of economic breakdown, I saw that building the new two reactors was perhaps the only way.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to go to a clip, another clip of Nuclear Nation, that gives us a little background on the town of Futaba.

MARC CARPENTIER: Futaba’s farming history goes back over a thousand years. In winter months, people had to leave town for work in the city. Reactors 5 and 6 came online in 1978 and ’79. Money flowed in from the government, and the townspeople found themselves with lots of extra cash. They built roads, a library, a sprawling sports center, and made major upgrades to the infrastructure.

AMY GOODMAN: Nuclear Nation, talking about nuclear refugees, the nuclear refugees of Futaba. And we’re joined by the former mayor, who made the decision, on his own, right after the earthquake, to move his entire town, to evacuate it to Tokyo, being deeply concerned about the levels of radiation and feeling that the government was lying to them about the dangers in the area. This was a mayor, Katsutaka Idogawa, who was fiercely for nuclear power, was proud to be able to get two more reactors in his town to build the economy, to get tens of millions of dollars, and then turned around after the meltdown, after the earthquake, the tsunami and the ultimate meltdown of three of the six existing reactors.

Mayor, right now, you are not the only one who turned around in office. Naoto Kan, the prime minister, also a fierce proponent, is now speaking out all over the world against nuclear power. But just this week, as we flew in to Japan, the government of Prime Minister Abe, the most conservative government since World War II, announced that it wants to build more reactors in Japan. How are you organizing? What are you doing now?

KATSUTAKA IDOGAWA: [translated] Without being able to even deal with the consequences of the Fukushima nuclear disaster, the position to promote nuclear power still is something which is just unthinkable to me. And I believe it’s really important for the prime minister to look at what he’s actually been responsible for and have regret and really deal with what they have done, before they can actually go forward and do anything. And the disaster now is bigger than anything we can cope with. It’s a disaster on an international level, and huge consequences, so he needs to really recognize this.

AMY GOODMAN: So who’s driving the push for more nuclear power? The country, already 30 percent dependent for its energy on nuclear power, had plans to make the country more than 50 percent by 2030. But after this catastrophe, who is pushing for these nuclear power plants?

KATSUTAKA IDOGAWA: [translated] The nuclear power system is constructed to use huge amounts of public tax. And this is a very tasty, shall we say, position or situation for the large corporations. They were really behind this push. However, much public taxpayers’ money is being used behind this. And I believe it’s so important to prevent our taxes from being used for any of this kind.

AMY GOODMAN: What has happened to the Fukushima refugees today?

KATSUTAKA IDOGAWA: [translated] There are so many people who want to evacuate but don’t have the means to be able to actually do that and are still living in this situation, who want to do something, but they have no support. And another huge issue is those who are still forced to be living within the greater Fukushima prefecture area do not have access to full health measurements, health treatments, and the kind of support that they need. And they’re also told that any diseases or sickness that they have is not caused by radiation.

AMY GOODMAN: You are traveling the world. Can you tell us the countries you’ve been to and why you’re speaking there?

KATSUTAKA IDOGAWA: [translated] I’m working with people all around the world, speaking with people who are working against nuclear power in their own areas.

AMY GOODMAN: You went to Finland?

KATSUTAKA IDOGAWA: [translated] Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: Why?

KATSUTAKA IDOGAWA: [translated] I went to Finland to speak with people who are working against the construction of nuclear power plants in their areas, because they knew our situation and what happened to us, and we’re trying to work together to prevent this from ever happening to them.

AMY GOODMAN: In the United States, a nuclear power plant has not been built in close to 40 years, very much because of the anti-nuclear movement and the cost of what it means to build a nuclear power plant and what to do with the waste. But President Obama has talked about a nuclear renaissance and is pushing for the building of several new plants for the first time in decades. What message would you share with him?

KATSUTAKA IDOGAWA: [translated] The nuclear power disaster is not just of Fukushima. This is a disaster of all humanity, of the entire world. There is a Japanese saying, and its meaning is that, well, any kind of disaster, three times is the limit. And we have had the three large disasters: one in the United States, one at Chernobyl, and now Fukushima. The Earth will not be able to cope with any further nuclear disasters. For the children of the future, the future generations, I hope that we can stop this now.

AMY GOODMAN: What is the alternative?

KATSUTAKA IDOGAWA: [translated] Well, I’ve heard in U.S. there is shale gas, for example. But as well as other forms of energy, I believe it’s also very important now to look at how we can have lifestyles that rely less on energy, that use less energy more efficient in our homes and in our offices. And Prime Minister Koizumi is also suggesting this.

AMY GOODMAN: Prime Minister Koizumi, very significant that a conservative former prime minister also came out against nuclear power.

KATSUTAKA IDOGAWA: [translated] Even he looked at the actual situation. And I believe that Prime Minister Koizumi really visited places affected by nuclear power to really see what is happening, and he’s really speaking sincerely now.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to thank you very much for joining us on Democracy Now!, Katsutaka Idogawa, former mayor of the town of Futaba, where part of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant is located. The entire town was rendered uninhabitable by the nuclear meltdown. This isDemocracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. Stay with us. After break, crowdsourcing radiation monitoring. We’ll look at how a group called Safecast has helped Japanese civilians turn their smartphones into Geiger counters. Stay with us.

source: DemocracyNow.org, summary translation: DemocracyNow.jp